It’s only come to my attention recently how guarded I’ve become with touch and seemingly innocuous access to my body. Like most things, in the moment I don’t realize what’s happening but upon reflection, there’s a clear pattern.

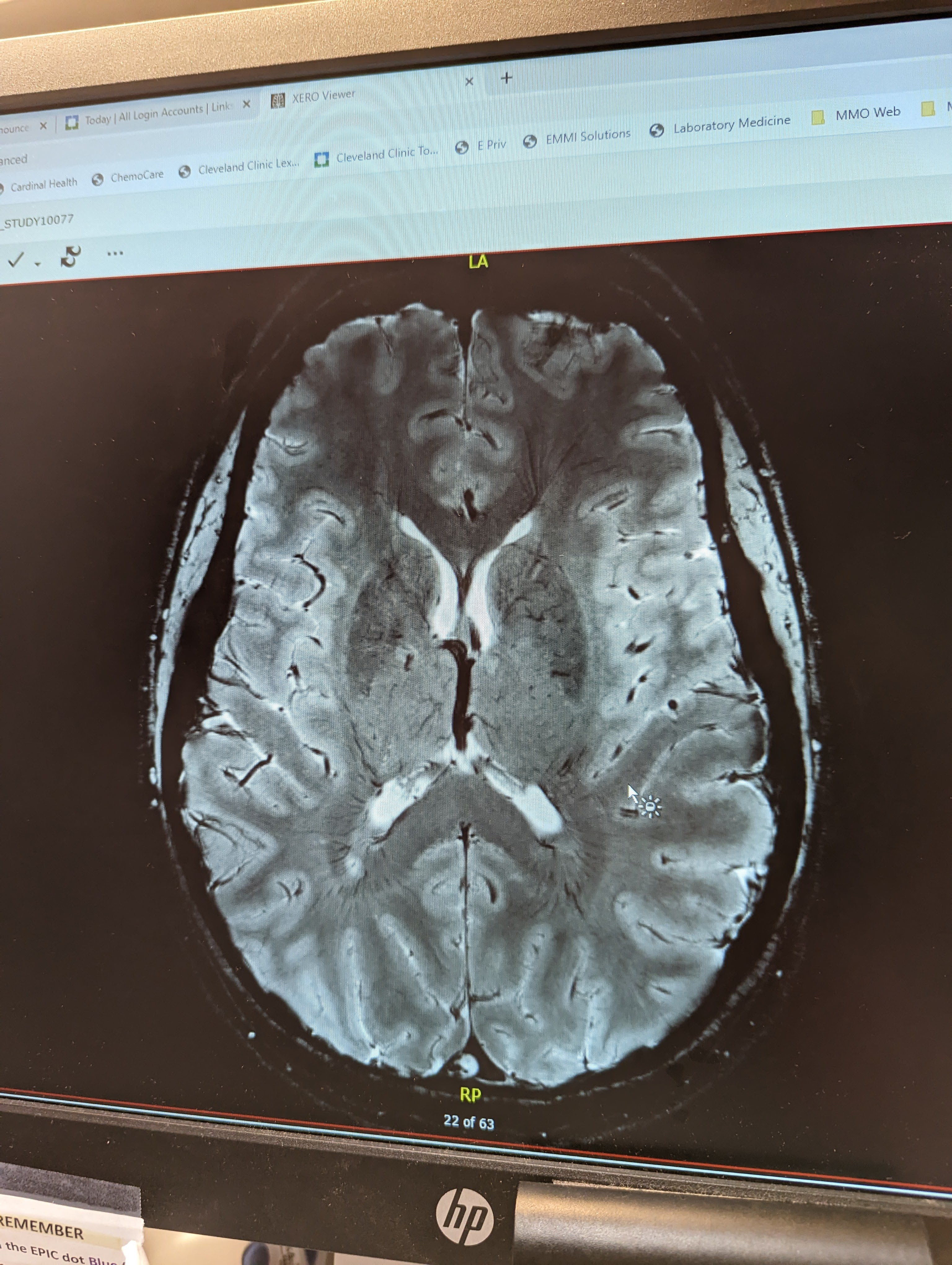

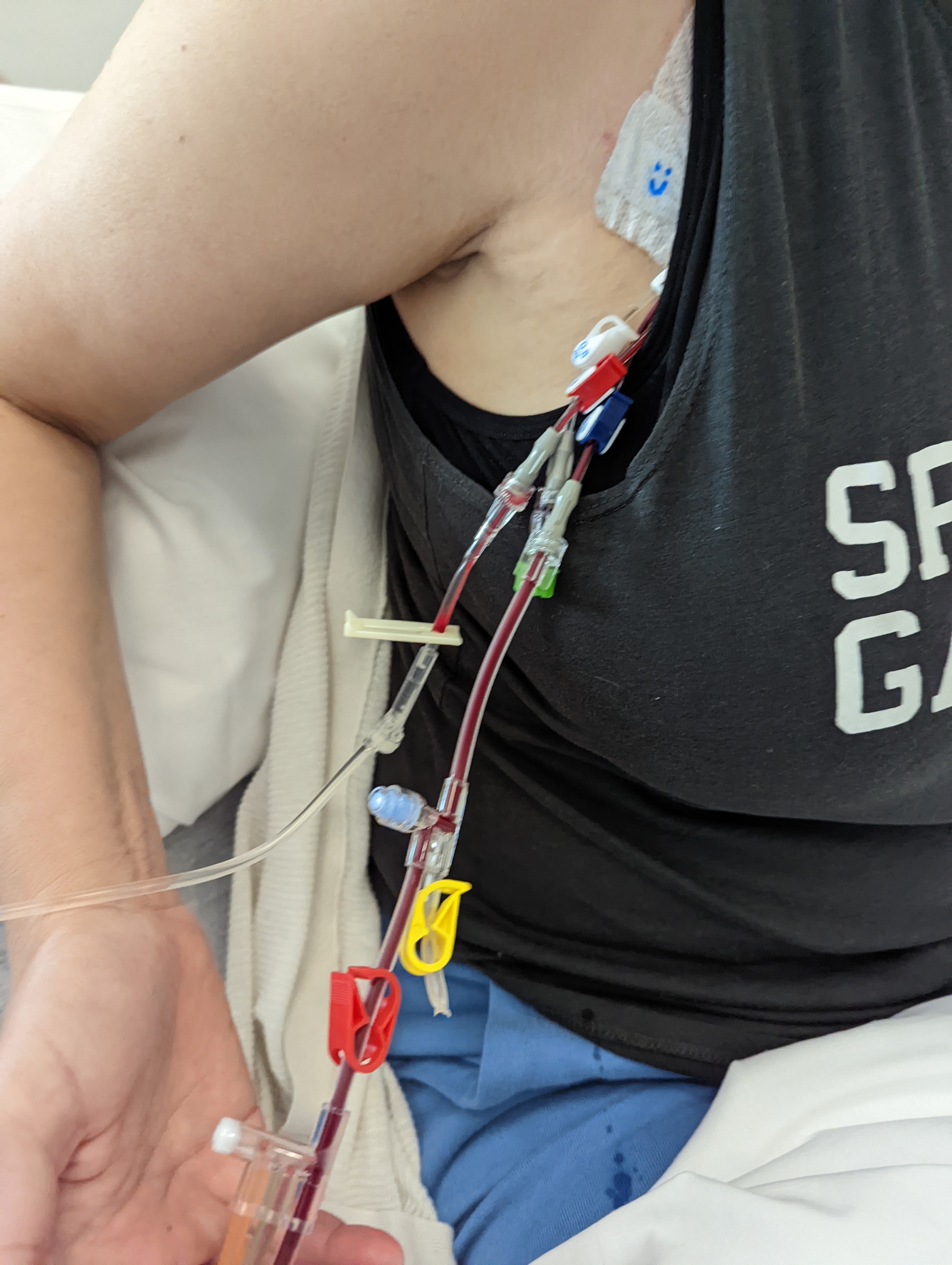

Several things happened all at once and I would be remiss not to mention the interplay of them all. As much as I would like to extrapolate and blame one person, one thing, that isn’t the case. My marriage declined as my disability increased. That happened simultaneously with the pandemic and intense and prolonged isolation from neighbors, family, and friends. I also signed up for the whirlwind of HSCT that increased my medical appointments, tests, labs, follow ups, and hospitalizations exponentially.

The medical contract

I’ve spent the last two years being poked, prodded, and touched. I’ve been told to push down, pull up, push back, force, try, think, do… over and over again as if the request might alter the final result despite my broken nerve connections and neurodegeneration. I’ve had strangers’ fingers touch the sides of my body — face, arms, legs, shins, and feet to test if sensation is the same on each side. I’ve endured safety pin pricks and tuning fork vibrations. I’ve had my blood pressure and temperature checked three million times, on the hour. I’ve been given shots to prevent blood clots.

I’ve endured endless beeping from loud and persistent chemotherapy pumps, flashing sirens of ambulances, stringent smells of antiseptic, and the disgusting feel of latex gloves. Over and over and over again. I’ve had to tell my story, my history, recite medications, advocate for my needs. I’ve been forced to accept that nobody has an answer for why my body behaves the way it does. I am an anomaly, an unsolved mystery in medicine. They don’t have drugs or therapies that help me yet. They’re working on it. I’ve never been a patient person.

The need for human connection

We need community and people. We need hugs and holding hands. We need gentle touches and caresses. We need connection. But the most important thing for me, is that now I realize I need agency over when, where, and how I receive that connection. And in medicine, that agency is lost. Your independence and decision-making power are handed over when you sign on the dotted line. You’re handing over your bodily autonomy in the hopes that the doctor is smarter and can make sense of the body you inhabit. I signed the contract. I made the choice, but you can’t know what you’re signing up for. In the beginning there was hope. In the middle there was confusion and pain. Maybe now there is a degree of acceptance. I’m hoping and leaning towards transformation in the near future. I gave my body to science and I’m trying very hard to get it back.

I did it all and I did it willingly. But looking back I can see the harm, the trauma, the changes caused. With each appointment I became more resigned to my fate. The tests inform the medical team but at a high cost. I had no right of refusal because I needed the information gleaned. But with each poke, prod, and touch of a stranger, my armor got thicker. Unbeknownst to me, my barriers were up and getting stronger each day. If I had to be touched by medical personnel, then I exhibited some control over the people in my life by saying no to hugs and comfort. I overreacted by removing myself from the kind and healing touches.

At a work gathering in January, a colleague I was meeting for the first time approached to give me a hug and I stopped her, proclaiming that I wasn’t a hugger. But that isn’t true. I am a hugger. I like holding hands. I crave touch. I’ve always been a proponent of body work – massage, acupuncture, chiropractic, yoga, reiki – you name it, I’ve done it. I remember my sister massaging my feet in the hospital as I could barely move and thinking it was the most precious gift. My dear friend and masseuse rubbing soothing oil into my bald head calming the pain and my racing thoughts. During last year’s travels, my companions lifted my legs or adjusted my feet to increase comfort and offer their assistance.

Someone else had the words

I recently watched a documentary about David Holmes, Daniel Radcliffe’s stuntman on the Harry Potter films — a story I never knew. If you haven’t seen it, please give it a watch. I found myself extolling aloud wondering how can he be so kind, so calm, so grateful? At one point (and I’m paraphrasing his beautiful words) he mentioned the feeling of being trapped in his body. Tears ran down my cheeks as I nodded along. Then he said the most sucker-punch statement I’ve ever heard. He described the feeling of going to sleep each night wondering what won’t work when he wakes up in the morning. He put to words feelings I had never described. He detailed the root cause of the majority of my fear and anxiety.

Putting in the work

I’m working really hard right now to think of my body as functional, beautiful, and perfect in its imperfections. I’m working to feel safe with medical professionals rather than tense my muscles and flinch when touched. I’m dating again and learning to articulate what I need but also understanding that my body is unpredictable. I’m trying to be patient, but I want to get to the part where touch equals pleasure, not pain. I want to have positive associations with my body, not negativity and trauma.

There are some in the community who accept and find joy in their disability, and they do this with grace and ease. I am not that person. I miss movement. I feel trapped in my body. I resent my illness. But I’m trying, and that’s all I can do. I am reframing in my mind what is possible. I am separating facts from feelings. I am opening myself up because with vulnerability, I have the potential for joy.

I don’t want to carry the armor any longer. I think two and a half years is long enough. Walking is difficult enough without the burden of my disappointment and fear. I don’t want to resent the body I inhabit. I want to appreciate the hard work and terrible working conditions it gets through each day. I want to celebrate the movement and the mobility I have, rather than focus on what was lost. I want to give people the chance to connect through touch. I get to choose rather than resignation to the inevitable. I want to compartmentalize the medical world from the rest of my life rather than it be my whole life and my identity.

I’m consciously taking off the suit of armor and laying it down. It’s not wanted or needed any longer.

How to stay sane in the hospital

- Noise cancelling headphones

- An eye mask

- Loop ear plugs

- Silk pillowcase

- Soft blanket

- Your own clothes

- A go-bag of toiletries (your own skincare and toothbrush will provide emotional support)

Yes, you can bring these things to the hospital and yes, they actually help. I would also add audio books and a kindle to that list, but I think by now you know I don’t go anywhere without a book.

One response to “Armor”

Carolyn, I was really touched by this post. I was also a little stunned that we both wrote about armor this weekend, possibly at the same time? I was journaling on the subject on Sunday afternoon, thinking of what it means to have emotional armor when you need it. A completely different approach, but so interesting, the timing! I ended up writing about psychological aspects of resiliency and then found myself learning about the Inuits, who live in such a harsh environment. It led me to learn about their spiritual beliefs and myths and I was really fascinated. I thought I would write something that tried to capture the magical feeling in their stories, animal spirits, and the beauty of their land. How did this evolve from armor? Our minds are funny, lol! Anyway, I really enjoy your blog, and I respect how you share your thoughts and feelings, it’s a brave thing. Take care, Michelle

LikeLike